By Kim Robson:

How often have we seen a dramatic television or movie scene where someone flushes a bunch of pills

down the toilet? Yay for sobriety, right? It’s almost a cliché. But the environmental impact on animals and microorganisms of pharmaceuticals in rivers, lakes and drinking water can be devastating.

Some pharmaceuticals can affect bacteria and animals at concentrations well below those used in safety and efficacy tests. Combinations of different compounds, aka the “cocktail effect,” may have unanticipated and understudied effects on the environment. For instance, doctors warn patients about mixing ibuprofen with beta-blockers, but a fish swimming in a soup of drugs and chemicals in a polluted lake doesn’t have that option. Multiple kinds of similar drugs could also create an additive effect.

For example . . .

In Lake Michigan, high levels of the diabetes drug metformin were found. The effect on lake fish was that a gene related to egg production was being expressed in male fish, indicating hormonal changes. Metformin could be having a feminizing effect on male fish, decreasing their ability to reproduce.

Between 1996 and 2007, millions of vultures in India were killed by exposure to the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac, driving the birds nearly to extinction. The drug had been given to cattle to treat pain and fever, and because people in India do not eat beef, the carcasses of dead cattle — including cattle recently given high doses of diclofenac — were left for vultures to feast on.

Between 1996 and 2007, millions of vultures in India were killed by exposure to the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac, driving the birds nearly to extinction. The drug had been given to cattle to treat pain and fever, and because people in India do not eat beef, the carcasses of dead cattle — including cattle recently given high doses of diclofenac — were left for vultures to feast on.

The veterinary anti-parasite drug ivermectin has been found to reduce the number and variety of insects in cow dung, which can delay dung decomposition and potentially reduce the amount of food available to birds and bats.

These aren’t just isolated cases, either.

A 2014 global review of pharmaceuticals in the environment commissioned by Germany’s environment ministry found that, of 713 pharmaceuticals tested for, 631 were found above their detection limits. Pharmaceuticals were found in the environment in 71 countries across all of the United Nations’ five regional groups, mainly in surface waters, such as lakes and rivers, but also in groundwater, soil, manure, and drinking water.

The worst drugs (such as antibiotics, antidepressants, anti-inflammatories, analgesics, beta-blockers, oral contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapies) have the potential to affect wildlife or people.

How are these pharmaceuticals getting into the environment? There are three main ways:

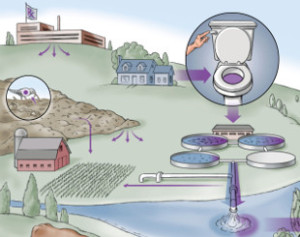

1 — By far, most of the drugs found in the environment have been ingested by people or animals and are subsequently excreted in urine or feces. As much as 30% to 90% of the active ingredient in an oral dose is not absorbed by the body. The metabolites of many drugs can remain active in the environment long after being excreted.

2 — The improper disposal of drugs comes in second — when people don’t finish a prescription or clean  out their medicine cabinet and flush leftover drugs down the sink or toilet. These drugs end up in sewage treatment plants, which are not generally designed to remove pharmaceuticals from wastewater. Depending on the drug, removal rates range from around 20% to 80%.

out their medicine cabinet and flush leftover drugs down the sink or toilet. These drugs end up in sewage treatment plants, which are not generally designed to remove pharmaceuticals from wastewater. Depending on the drug, removal rates range from around 20% to 80%.

3 — Finally, some drug manufacturing facilities release active ingredients into nearby waterways, creating localized hotspots of pharmaceutical pollution. In 2009, an environmental pharmacologist from the University of Gothenburg in Sweden found high concentrations of antibiotics downstream of several drug manufacturing facilities near Hyderabad in India. In some cases, the levels were equivalent to full therapeutic doses. Two years later, high levels of known antibiotic-resistant genes were found in the bacteria there.

While scientists are studying the effect of these drugs on the environment, we need to do our part to prevent the problem by properly disposing of unwanted medicines, improving sewage treatment and, ultimately, designing more environmentally friendly drugs.

Educating the public on the possible environmental effects of the contents of their medicine cabinets, and encouraging people to return unused drugs to any pharmacy for proper disposal is a critical first step. And perhaps ultimately we could learn to live with fewer pharmaceuticals in the first place by embracing more proven natural home remedies.

Kim Robson

Kim Robson lives and works with her husband in the Cuyamaca Mountains an hour east of San Diego. She enjoys reading, writing, hiking, cooking, and animals. She has written a blog since 2006 at kimkiminy.wordpress.com. Her interests include the environment, dark skies, astronomy and physics, geology and rock collecting, living simply and cleanly, wilderness and wildlife conservation, and eating locally.

Related Posts

-

Food Waste–The Perfect Choice of Imperfect Produce

March 9, 2019

-

Common Stainless Steel Cookware Mistakes

November 1, 2018

-

Here's What Going Green with Food Really Means

June 27, 2018

© 2024 COPYRIGHT © 2021 THE ZERO WASTE FAMILY™ - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED | DESIGNED BY REDEEFINED CREATIVE